Vicissitude, the quality or state of being changeable, is often used to describe the weather. The title is a tribute to philosopher Richard J. Bernstein, who wrote about philosophy’s “quest for some fixed point, some stable rock upon which we can secure our lives against the vicissitudes that constantly threaten us.”

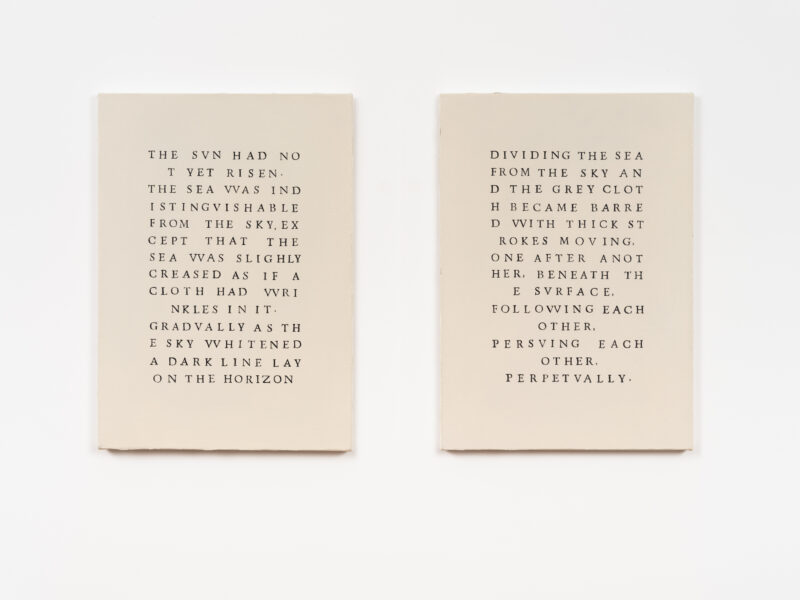

Mazza’s large-scale painting, Portent, on view at the gallery, comes with a kind of indescribable dizziness. This 67 by 87 inch painting absorbs the viewer into an unsettling yet mesmerizing scene, one that evokes a sense of vertigo. At first glance, the viewer may think they recognize what they see—a line, a color, the rippling surface of water… but do they really? Portent becomes a vast, absorbing expanse. Like the ocean itself it layers time, events, and emotions within it. The inspiration for Portent lies in Titian’s The Submersion of Pharaoh’s Army in the Red Sea, a 12-block woodcut from the 16th century. In both Mazza’s and Titian’s works, the water has already closed over the lost army, leaving only a calm, enigmatic surface. Mazza distills this historical reference into a landscape that meditates on absence, obscuring the line between past and present.

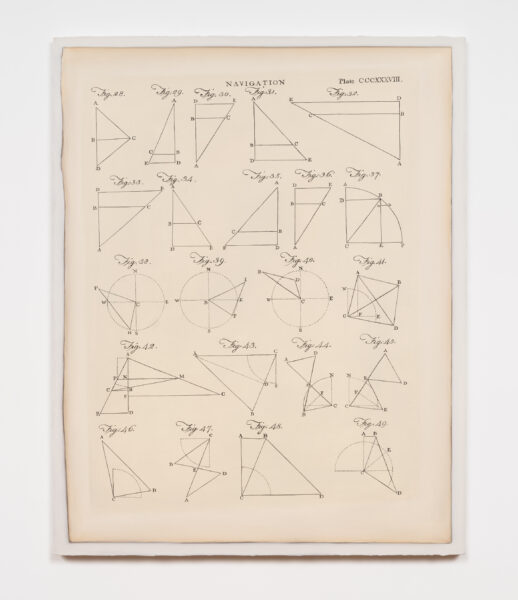

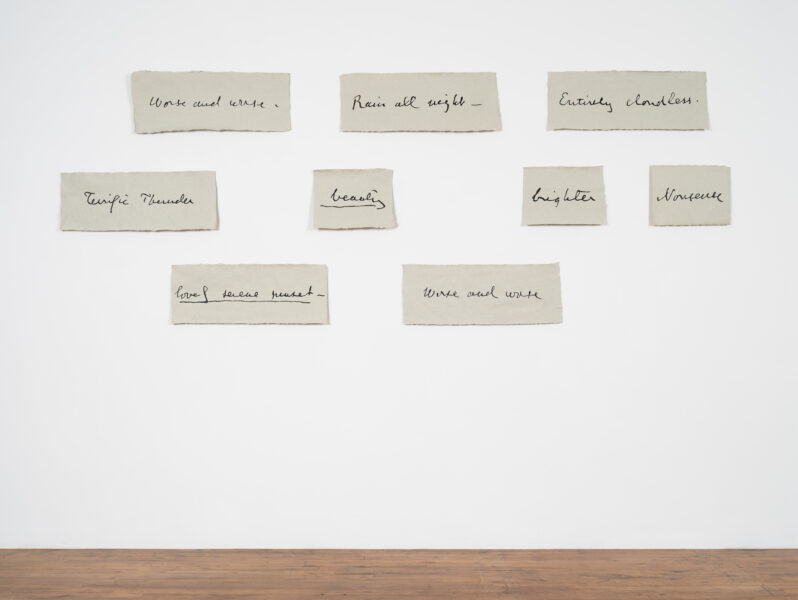

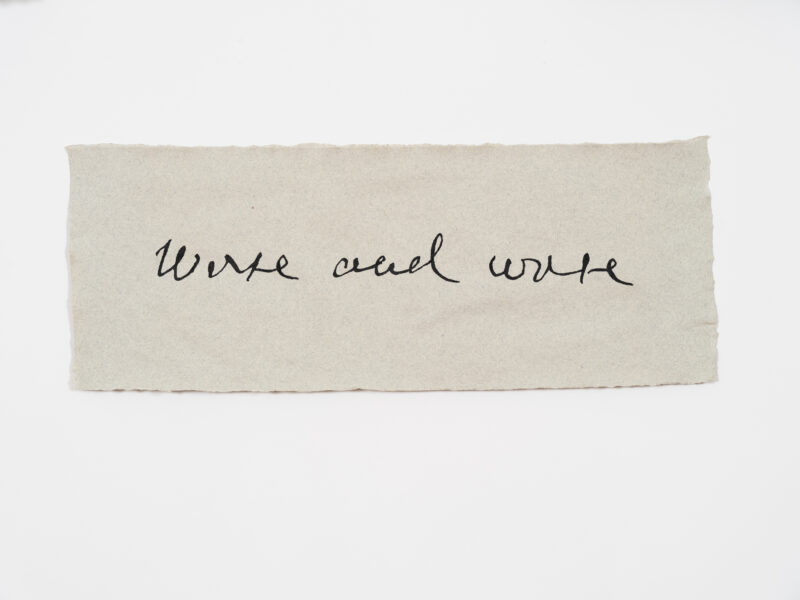

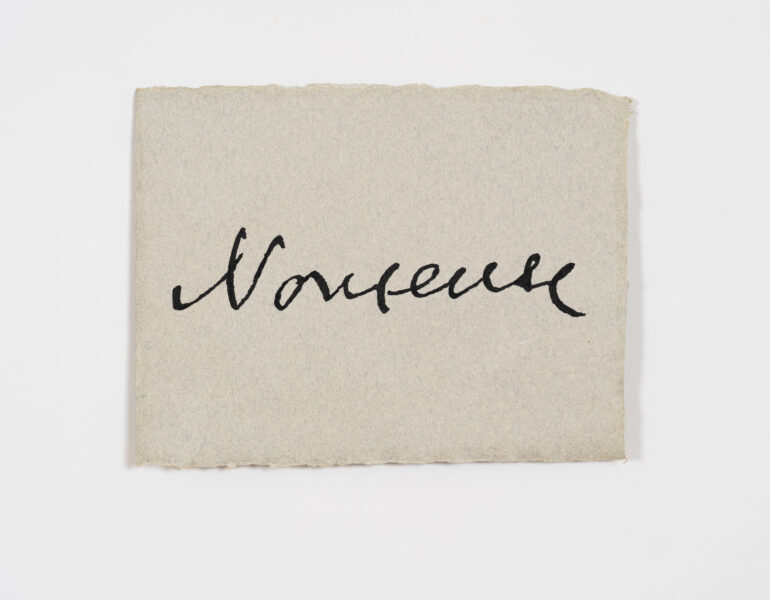

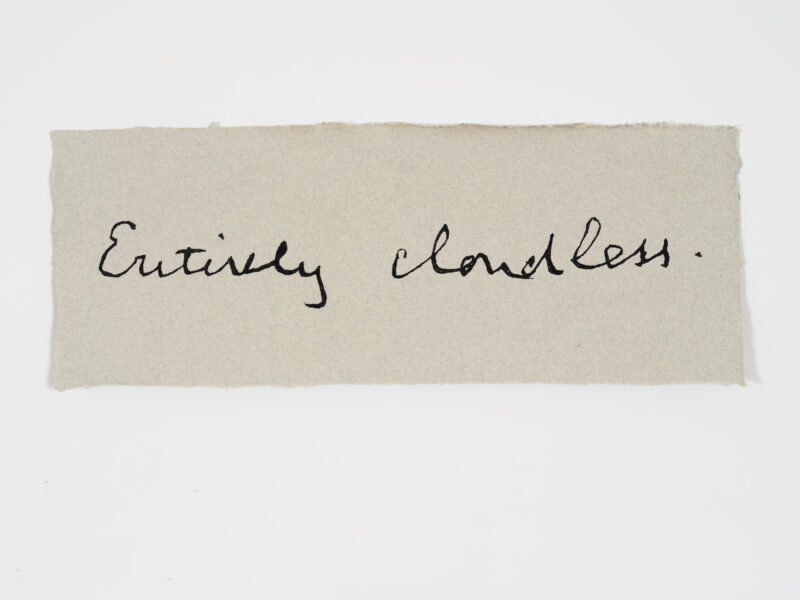

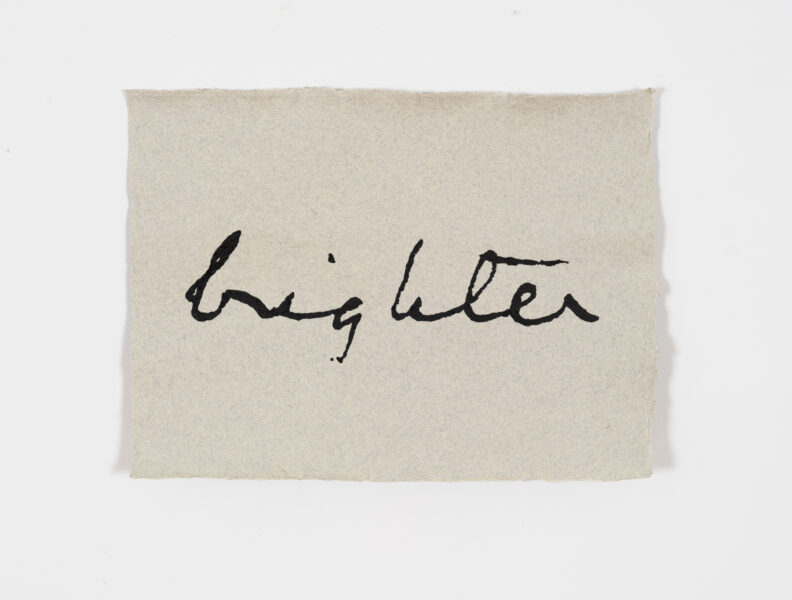

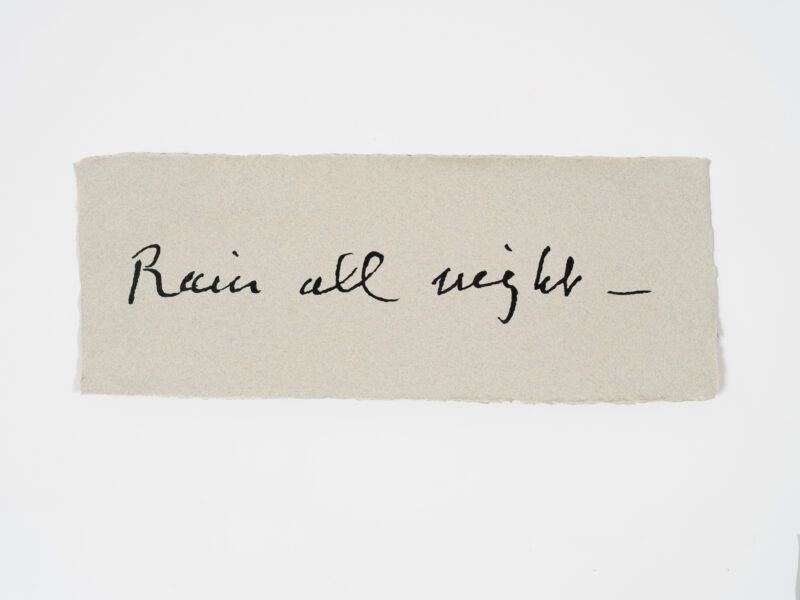

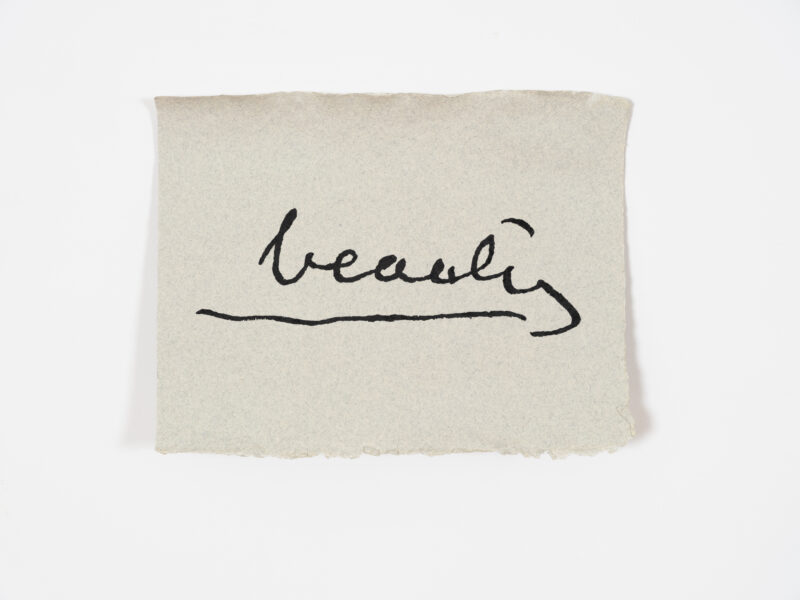

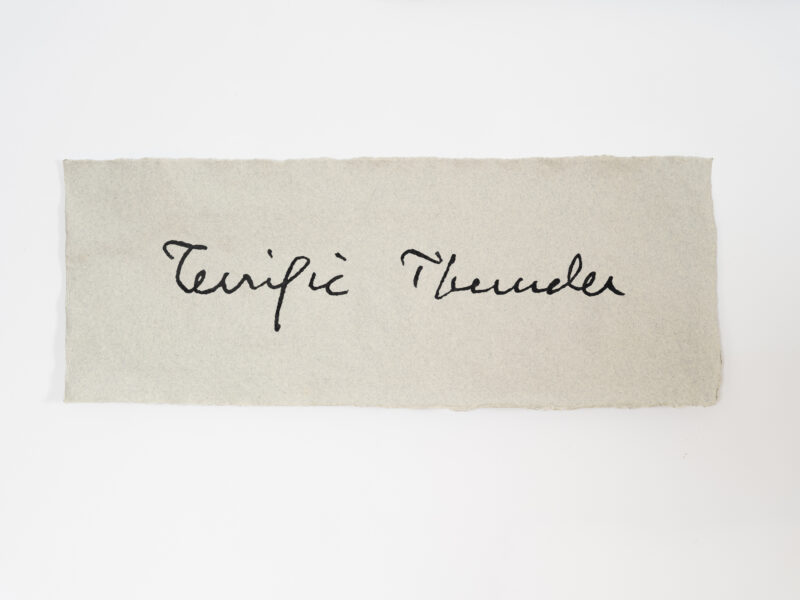

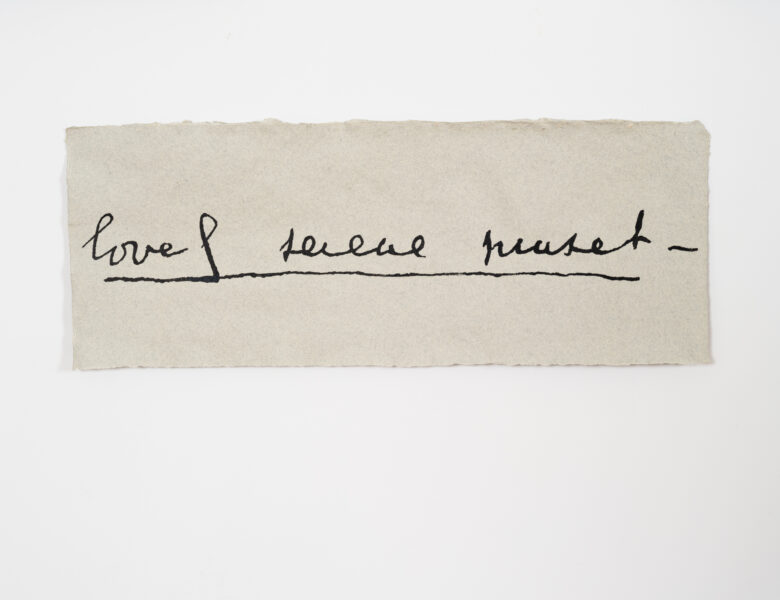

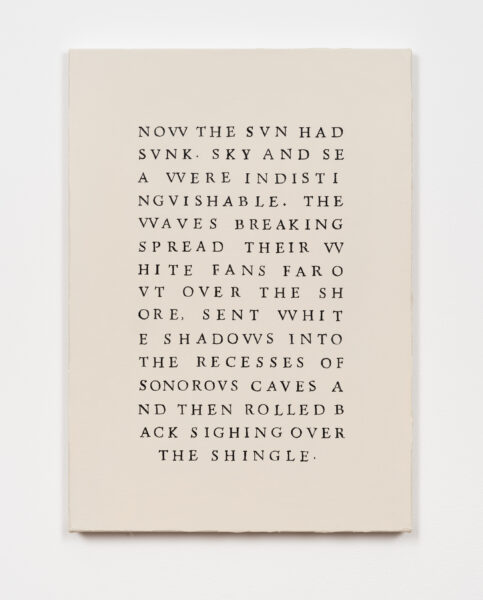

The works in this show are united through their connection with nature; many are drawn from historical images and texts, sources include Virginia Woolf, Abraham Ortelius and particularly John Ruskin. For the installation of works on paper titled Ruskin’s Landscape, Mazza culled texts from the manuscript of the British art critic’s Brantwood Diary (1876-1884). Ruskin’s record of nature’s unpredictability also becomes the record of his internal landscape and psyche. “Worse and worse” he writes on September 27, 1877 and he writes the same again on Sept. 28; while these dark spells feel interminable to Ruskin, he also describes momentary encounters with the sublime: “Rosey light on snow,” “Brighter,” and “Beauty.”