“Nothing touches me, nothing interests me, except what directs itself directly to my flesh”(Artaud, Art and Death)

“this unusable body made out of meat and crazy sperm”(Artaud, Here Lies)

The rain comes straight down, a curtain of rain outside the window. A city full of windows and so many contained, fleshy warm and bodied, behind each glass. Each room a box: window-paned, rain-curtained, enclosing its warm human fruit in degrees of ripeness or decay.

I wake at night and sense myself to be a knot of flesh, privileging one leg over the other – twisted and stuck out of the bedclothes. Another day and I sit in the park. The people on the grass nearby: asymmetrical and balanced on an elbow or pinning under a leg, seem to grow from the green like great fleshy blossoms, spring-pale and strangely foreshortened. Their bodies disjointed by a strip of bathing-suit or pair of shorts seem strange and unnatural on the lawn whose green goes on, unflinching, all the way to the corners of my sight.

I think of this experience of “otherness” as I walk through the Bacon retrospective. The way one’s self, or another person, can stick out like a thumb among fingers. It is the unmasking that interests me – not a gruesome breaking of bones and skin – but a cracking of the soul outwardly visible; sometimes in public, in a realization of extreme isolation in the midst of crowds.

“Vaguely alarming yet unreal, laden with consequence yet evaporating before the mind because not available to sensory confirmation, unseeable classes of objects such as subterranean plates, Seyfert galaxies, and the pains occurring in other people’s bodies flicker before the mind, then disappear.” (Elaine Scarry – The Body in Pain)

If there is an exposure that nails us to the rock of otherness in plain sight, it is that messy quality of emotion witnessed and uncurtailed. No matter how empathic one is, the suffering of others is always second hand.

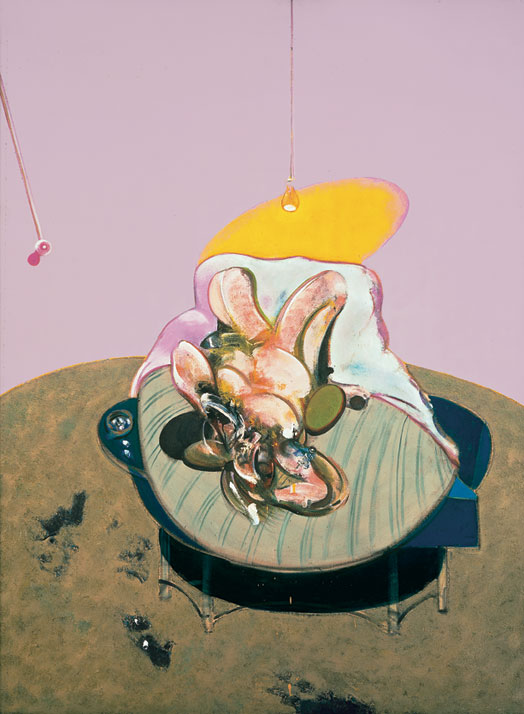

“When talking about the violence of paint, its nothing to do with the violence of war. It’s to do with an attempt to remake the violence of reality itself…the violence of suggestions within the image which can only be conveyed through paint…We nearly always live though screens – a screened existence. And I sometimes think, when people say my work looks violent, that I have been able to clear away one or two of the veils or screens.”(Francis Bacon in conversation with David Sylvester)

When Bacon says his work is not violent, not about violence, except for that everyday violence which comes from truly looking at the world – I believe him – knowing full well that the truth may lie in the opposite, as I have been told that Bacon sought violence out, created sympathetic scenarios which need not exist except to fulfill some sadistic urge – but I also know that some things emote better nameless, uncategorized, unsectioned. Bacon is an artist who has gone to great lengths to avoid a literal representation of things, so a direct narrative reading of his work seems to be like the syringe that pins down Henrietta Moraes’ fleshy arm in Lying Figure; “far too melodramatic”. As soon as the work becomes about a specific event in the life of another person we can isolate ourselves from its pure experience – and such knowledge tames the work.

For more than one reason Bacon’s statement reminds me of Proust, and more specifically it recalls Beckett’s essay on Proust: “The fundamental duty of Habit, consists in a perpetual adjustment and readjustment of our organic sensibility to the conditions of its worlds. Suffering represents the omission of that duty, whether through negligence or inefficiency, and boredom its adequate performance. The pendulum oscillates between these two terms: Suffering – that opens a window on the real and is the main condition of the artistic experience, and Boredom – Boredom that must be considered as the most tolerable because (it is) the most durable of human evils.”(Proust, Samuel Beckett)

There are of course other parallels between Bacon and Proust, the Baron de Charlus for example and the tendency to draw on lived experience, for though Bacon said: “my whole life goes into my paintings”, such a remark could easily have come from Proust. But I think there is something more interesting in a shared intention made visible through their work: a desire to use suffering as a means to break through artifice of reality and come closer to a sort of truth.

“The work of the artist, this struggle to discern beneath matter, beneath experience, beneath words, something that is different from them, is a process exactly the reverse of that which, in those everyday lives which we live with our gaze averted from ourselves, is at every moment being accomplished by vanity and passion and the intellect, and habit too, when they smother our true impressions, so as entirely to conceal them from us, beneath a whole heap of verbal concepts and practical goals which we falsely call life.”

(Time Regained, p 303)

Habit screens us from experience. “If Habit” writes Proust, “is a second nature, it keeps us in ignorance of the first, and is free of its cruelties and its enchantments.’ Our first nature, therefore, correspondingly, as we shall see later, to a deeper instinct than the mere animal instinct of self-preservation, is laid bare during these periods of abandonment. And its cruelties and enchantments are the cruelties and enchantments of reality. ‘Enchantments of reality’ has the air of paradox. But when the object is perceived as particular and unique and not merely the member of a family, when it appears independent of any general notion and detached from the sanity of a cause, isolated and inexplicable in the light of ignorance, then and only then may it be a source of enchantment. Unfortunately Habit has laid its veto on this form of perception, its action being precisely to hide the essence – the Idea – of the object in the haze of conception – preconception.”(Beckett)

We have forgotten how to look (or if we’ve not forgotten it must be a strategy of avoidance). Truly seeing is an overwhelming thing – there is too much. “If we had a keen vision of all that is ordinary in human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow or the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which is the other side of silence.”(George Eliot – Middlemarch)

Those born without the filters to screen out sight are like fires with too much oxygen – they burn all their kindling at once, and burn out. Bacon burned on into old age – but did his work burn out early? For burning the candle at both ends Artaud, Proust, Van Gogh – all proved to have short wicks.

Artaud posited that Van Gogh was not mad, but a kind of hyper-sane. He, the artist, the madman among the so called healthy, is the only one who truly sees. Taking nothing for granted the artist suffers from the exposure of a continual rebirth from which he emerges weekly, daily, in each instant – newborn – psychically naked and physically vulnerable, a living, breathing ecorche.

Bacon, following in the modernist tradition of Picasso, thought about how we perceive – not just with the eyes, but in a sort of sensory physical melting of ourselves over what we see; the way we externalize ourselves to absorb the world around us, not to mention the blurring of boundaries occasioned by sex, pain or drink – a slurring of one form into the next. In Bacon’s paintings the sharpness of edges is obscured by his brush or the mitigating presence of the glass, and they seem to suggest that both sight and memory are incomplete: what we see is influenced and perpetuated by our very presence. Every viewpoint implies not just a viewer – a pair of eyes, but a body which sees, a physical presence in the world, and in addition neither the creator, the subject, nor the viewer are static. Each of us is motion: the form on the bed, the hand of the artist petrified in the dried paint, the transitory figures reflected in the glass. The divide between one body and the next, between figure and ground, is not concise cut but a jittery trembling interstice.

Bacon’s figuration gives us a likeness, a nameable thing and then slowly it pulls the rug of expectation out from under us, bringing the viewer back to an initial, unfiltered presentation of reality. Bacon lifts the screens of Habit and shocks us into looking, he creates a visual misunderstanding that thwarts our expectations and so reminds of what we would not know – that we are meat upon the bone. “…let us submit to the disintegration of our body, since each new fragment which breaks away from it returns in a luminous and significant form to add itself to our work”(Time Regained, p. 315)

“And certainly we are obliged to re-live our individual suffering, with the courage of a doctor who over and over practices on his own person some dangerous injection. But at the same time we have to conceptualize it in a general form which will in some measure enable us to escape from its embrace, which will turn all mankind into sharers in our pain, and which is even able to yield us a certain joy.”(Time regained, p. 313)