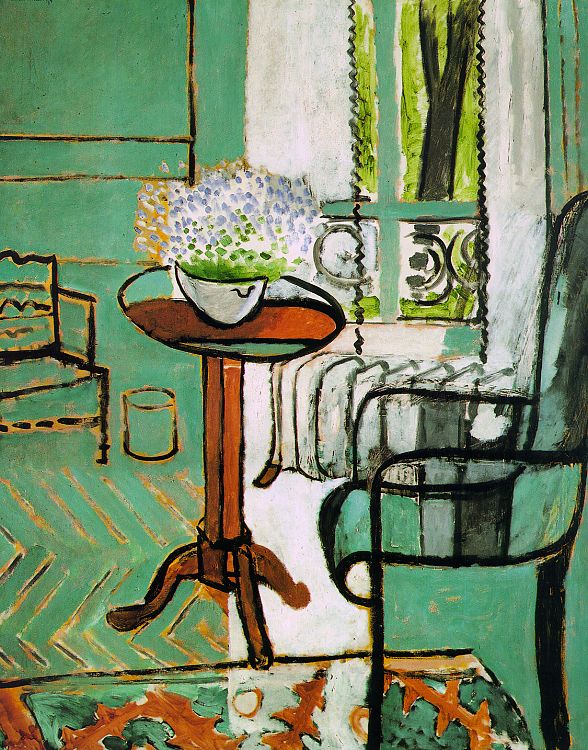

Matisse condenses the air – the light is form, the dark is form. What one would pass through is solid while concrete things are but interrupted flickerings; chains of lines flattened onto fields of bright color. Things that do not touch, except that the eye links them in their overlap, are pulled apart again or embedded in each other by an aura of unfinished air that does not blend form into form but holds them apart. This gap of unfinished canvas sews the objects onto the picture plane.

That things sundered by space or time are made to exist together – even to touch – in painting is a harmless enough lie; part of the painters’ art. But I cannot look at the Giacometti portrait of his mother without seeing how hard he tried to force the air back in – pushing it in between table and chair, wall and woman – so that suddenly there is air again for passing through. Before, behind, between, the space stretches back. In this art there is more truth – truth to explain how we see, if not what we see – than in paintings that present a truer likeness but subsist on a flattened plane.