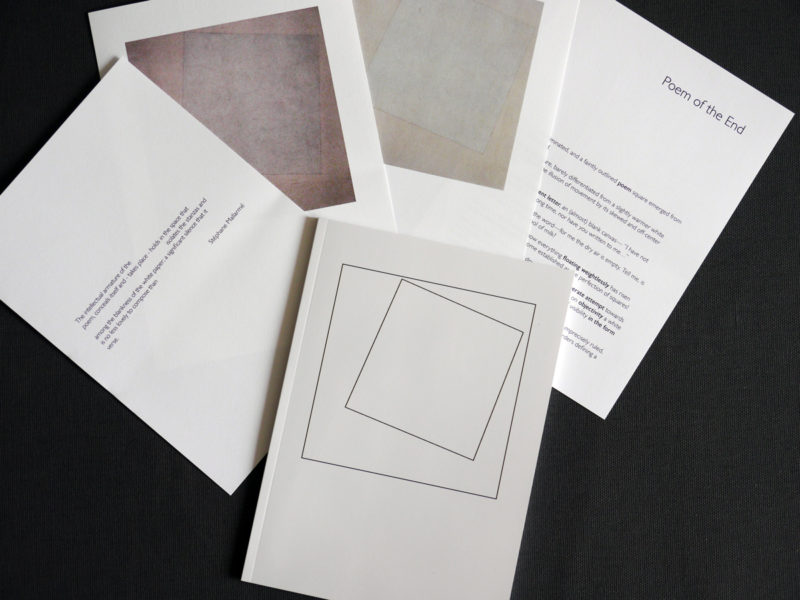

10 White Lies and Poem of the End: proof pages and printed and bound

white lie (n.)

an often trivial, diplomatic or well-intentioned untruth

a minor or unimportant lie, especially one uttered in the interests of tact or politeness

10 images from various web sources present 10 dramatically different takes on the original. All are identified as Malevich’s White on White, but few succeed well in their interpretation.

Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White was painted the year after the Russian Revolution of 1917. A white square floating weightlessly in a white field, it is an icon of the modern movement. Like a balloon Malevich’s square seems about to lift off, MoMA hangs the painting as did Malevich: high up on the wall in the space reserved for the Christian icon in the Russian home.

Malevich described his aesthetic theory, known as Suprematism, as the supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts. The color white was for Malevich the color of infinity, and signified a realm of higher feeling. And like the concept of the infinite, the ‘color’ of white has something intangible about it. Are we not told that white is the presence of all colors? White reflects back the whole of the visible spectrum. A color that is all colors and no color: white is a deceiver, a backslider, the double-crosser of the visible spectrum. Or else white is so credulous and wide eyed that it is taken in, easily influenced by its milieu: and so in the spectral scale it can be swayed and tipped in favor of one or another of its prismatic comrades. The perception of white is in fact dependent on, or influenced by the presence or absence of another color nearby. White tints itself to the light and becomes a pale mimic of whatever is near.

There are in fact two ‘whites’ in Malevich’s painting; the square of the canvas is filled with a warm, greyed out butter-toned white, while the interior square is cool, almost greenish by comparison. When standing in front the painting, one becomes aware of the artist’s hand at work, if dabbing may be called work? The impasto records each press of paint against the surface; repeated gestures that approach but never quite reach the penciled contour of the form that contains them. The use of white focuses the viewer on the tactile, on the paint itself. It seems accurate to say that amongst other possible interpretations, this is a painting about the very process of painting. Can a work that is so dependent on one language, the language of painting, be translated blithely into another form or material? The zero-form of painting, what would be the parallel, the zero-form of photography? A photo which could contain and reflect only itself might be the one whose existence is completely circumscribed by the darkroom, one which bears no image, but fixes instead one or another of the two extremes: either light or darkness…and of course such photos do exist.

Unlike many of Malevich’s other paintings which employ more contrast in the artist’s choice of palette, it is the subtlety of this painting which I believe makes its reproduction so very difficult. And could the reproductions hope to contain much of the original experience? Is this assumption not like that of the 19th century photographers who claimed to capture the spectral auras of the dead, or to be unbiased judges of reality through this impartial lens, the eye of technology? Or is the truth not in the medium of translation, but in the skill or authority of the translator; in the accuracy of the translation, in it’s likeness to the original and it’s authenticity? And how do we judge that likeness?

What then does the photograph offer us of an original? In this conversation I cannot avoid mention of Walter Benjamin: Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be. He speaks of aura and authenticity for which the photo is no great container. The photo is anemic, the essence of the object has bled out of its representation. Still, the photograph is a document of sorts, a guarantee of the existence of the original, but in a medium which can be manipulated in so many ways, both intentionally and accidentally, it is not necessarily a simple and accurate document of the object it represents. The photo is fact contingent upon multiple concurrences in which each element contains a variable which could alter the finished product.

The photo is the result of, and so documents, a confluence of place, object, light, camera and photographer. It tells us that a viewer, the photographer: a double who must serve as our eyes, did in fact stand in for us at some particular instant and when a button was pushed an aperture did open and the light reflecting from the object before that eye staring through that camera, did rush in through that pin-hole and touched…what? The film? Yes, the film, or its equivalent. The result is not virtual, the photographer did in fact witness what he now asserts in the form of an image, a photo, a reflection of the original.

And what is the truth after-all? Is photography the representation of, or simply the guarantee of the original? If the photo is a lie, then surely it is a white lie; but in the interests of tact, what is missing? What has been left unsaid? Some of the images I have included are ridiculously duplicitous, mere parodies of the original, others are more accurate, and among them, but I won’t tell which, is MoMA’s own digital presentation of the painting from its collection. Which lie will come closest to the truth? What harm is done by their inaccuracy? Which will access Malevich’s pure feeling and perception: the trace of the sublime contained in the original?