“At certain hours of the day the countryside is black with sunlight”

Camus (Nuptials at Tipasa)

“Dark with excessive bright thy skirts appear”John Milton (Paradise Lost)

“I am beginning to use pure black as a color of light and not as a color of darkness.”

Henri Matisse

Je plongerai ma tête amoureuse d’ivresse

Dans ce noir océan où l’autre est enfermé

Charles Baudelaire (La Chevelure)

Helping me to take photos in a dark room, my friend Emma asked what sort of darkness I wanted to achieve – deep dark, shallow dark? How many darks? Low ceilinged dark, watch your head dark, near to the wall dark, bump your shin dark, inside dark, outside dark? How deep is dark? Something perhaps more considered when black and white is your medium.

Beginning painters are told to avoid black. They are told to mix a sort of faux black which is usually the oily blue of Pthalo with Alizarin Crimson. But I have a fondness for black paint, but still I do find it difficult to manage. When wet black oil paint is a slick squiddy butter that appears to coat all with its near perfect opacity, but when dry it has an imperfect sheen: it shows what is underneath, here sucking the light, here giving it back. Used in small quantities it is better behaved. I like to paint flowers using black paint, I like the irony of it. No, nothing funereal, instead a posey of yellow roses, pink peonies and small white rose-buds, dahlias or marigolds: black mixed with vermillion is a red petal seen from underneath with the light passing through it – the color glows like a lamp. Blacks are incendiary colors – burnt things, the carbon left behind: lamp black, that oily soot caught above the flame. Thinking of mothwings trembling then stilled. There is gas lamp black and oil lamp black, Ivory black, Vine black, Mars black, Scheveningen black, Black Roman earth, German earth, Slate black.

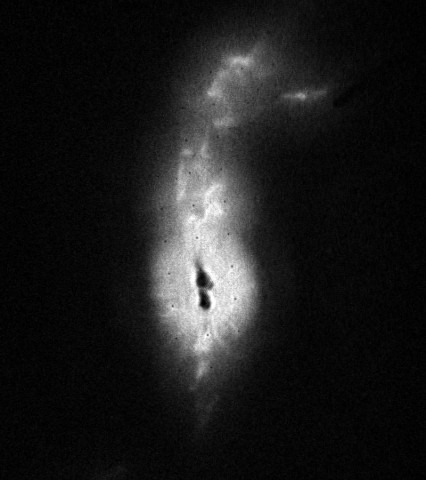

I have long been fascinated by the way a black thing in a lit space eats the light, disrupts space, becomes a hole. Even the starling, who up close shimmers with a multicolored iridescence, is at a distance a flat black cutout against the landscape.

Black is Manet and Velazquez. Black is Goya witches and cloven hooves. Black is Matisse.

Black is tiny beady rat eyes. Black is my cat. Black is driving through the Texas panhandle on a moonless starless night. Black is lava stilled, blood congealed, ash, asphalt or caviar. Black is hair combed and slick. Reading Gracq’s Dark Stranger I imagined the debauched and charming devil polluting the seaside resort to have hair like black oil. In Blue Eyes, Black Hair Duras’ heroine sleeps naked on the floor but for a black cloth over her face. From under the darkness she can hear the sea.

Black is the sea I walk along at night. What seemed in blue day to be welcoming and bright now threatens. How black the water, breaking the reflected light into fragments, into little quivering shards that struggle to assemble but cannot. In the rush and surge of the waves, one measures distance by sound. Sound and the saturation of the sand underfoot; here nearest and under-waves is soft and giving-way, here further and outside the ocean’s margin of influence is dust. But I like to walk along that dense spine between soft and soft. I am reminded of Pavese’s Political Prisoner, who in a small isolated village, looks out of the hut in which he must serve his sentence, sees the sea and knows it to be a wall: an insurmountable wall, more so still than in any prison.

Navigating the edge between land and sea is like walking with death on your left hand. It is the unknown. It is a wall because you cannot see into it, but it is a devouring wall. To venture into the waves by night is walking into blindness, into death. I feel a quickening in the swirl and am fascinated to watch the water swallow my feet and ankles but I go no further. Each step is a battle against my sense that the abyss lies just beyond my toes soft hold and if the water lifts me up my sinking faith will not sustain me.