Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at the Huntington

GREEN

The pointed fingers of glass hang downwards. The light slides down the glass, and drops a pool of green. All day long the ten fingers of the lustre drop green upon the marble. The feathers of parakeets–their harsh cries–sharp blades of palm trees–green, too; green needles glittering in the sun. But the hard glass drips on to the marble; the pools hover above the desert sand; the camels lurch through them; the pools settle on the marble; rushes edge them; weeds clog them; here and there a white blossom; the frog flops over; at night the stars are set there unbroken. Evening comes, and the shadow sweeps the green over the mantlepiece; the ruffled surface of ocean. No ships come; the aimless waves sway beneath the empty sky. It’s night; the needles drip blots of blue. The green’s out.

—Virginia Woolf

Was green the first color of perception?

—Derek Jarman

.

In this moment when I am confined to my apartment and museums and galleries remain closed, I find myself reflecting on exhibitions I have visited over the last few years. But no, that is not exactly true, at this very moment I am thinking, truly aiming my mind at a specific color of green. This green fills the background of a painting, well, two paintings, a diptych that I saw last year. Already I have nearly spoiled my idea of the color by pulling up images on my laptop that do not make comparison with the ones in my mind, no, none of these digital copies match my memory of the work in question.

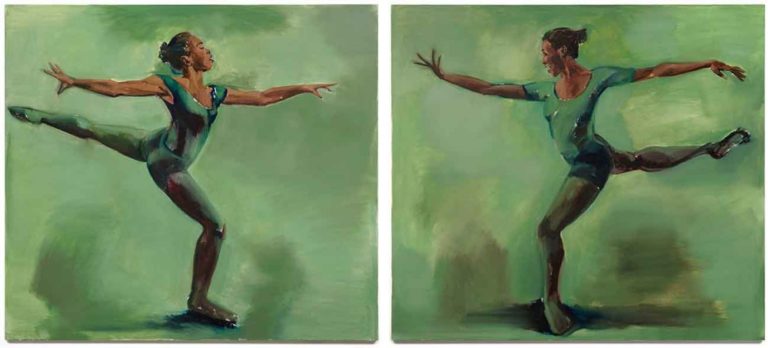

When I think of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s exhibition at the Yale Center for British Art, which I saw on November 30th of last year, I first recall the color green; the diptych Harp-Strum taking up most of my imaginative space and more wall than any other single work. I see it hung with a window to its left and daylight suffuses the wall and the paintings. There is something about this color of green, which I hesitate to translate into words for fear of influencing my memory of it.

When I look up the Yale show online, I see that a select group of works continued to the Huntington Library in San Marino California. The Huntington houses not only library, but also an art collection, including the most important collection of British grand manner portraiture outside the United Kingdom, and is surrounded by 120 acres of botanical gardens. The museum has been shuttered since mid-March, and the exhibition of Yiadom-Boakye’s work—which opened in late January—was to close on May 11th. A talk by the show’s curator, Hilton Als, provocatively titled “The Red and the Black” which was to be held on the evening of March 17th was cancelled as this date coincided with the closing of the institution.

In search of green I walk to Stuyvesant Square Park, twin parks that flank 2nd Ave below East 17th Street. Both gardens are full of new green growth, it has been a cool wet spring, and now as the temperatures rise it grows shady as the trees fill out. Since the ‘pause’ began, nothing has been trimmed, mown, or weeded, so the cultivation goes a bit soft around the edges, especially in the easternmost park which always seems a little forgotten, a little wild. I wonder if the gardens at the Huntington are in the same state, by which I mean on their way to being exuberant and maybe even a little rank and seedy (Et in Arcadia Ego…). As I mentioned it is still spring here, and there is a general softening of geometry as new shoots round out old hedges; and the all various greens and the complex luminosity of new leaves, which are still soft, the way young skin is, the way wet oil paint is; the way it breathes, reflects, and absorbs light, and the sun makes these new greens go transparent as sea glass.

I have never visited the Huntington, but can imagine walking on garden paths and tracing a line between cultivated nature and the cultivated uncultivated nature that exists in the backgrounds of portrait paintings in the grand style and other 17th-19th c. European paintings in their collection. These painted gardens grow romantically twisted trees that caress baldly behind Gainsborough’s prim Woman with a Spaniel, and also grow secluded woods as in Watteau’s The Country Dance – shadow, vine, and moss; pink roses bloom so heavily on the bush that branches tip towards the ground and spill into van Dyck’s portrait of Anne Killigrew Kirke.

Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings are installed in a row in the foyer just outside the Thornton Portrait Gallery—where many of these portraits are housed—and across the way in the antechamber is the van Dyck portrait with Anne and her roses. (I am thankful to Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times for the “picture” he writes of the installation.)

There are 5 works in this show:

Greenhouse Fantasies, 2014, oil on canvas, 28 x 24 in.

The Needs Beyond, 2013. Oil on canvas, 14 x 12 in.

Harp-Strum, 2016. Oil on canvas, diptych: 71 x 79 in. each.

Brothers To A Garden, 2017. Oil on linen, 59 x 48 in.

Medicine at Playtime, 2017, oil on linen, 79 x 48 in.

Figure 1- Harp-Strum

Among the five paintings—which I can imagine still hanging on the walls at the Huntington—are three: Harp-Strum, Brothers To A Garden and Medicine at Playtime, where the figures gaze is directed away from the viewer, only in Medicine at Playtime does this seems a redirection, a breaking of the gaze. In the others there is a negligence towards a ‘viewer’. As in Harp-Strum, where the depicted dancers, while presenting us with such poise, seem to be deriving their balance not with the idea of being seen by us, but well past the mirror stage each woman seems to feel her way into the pose from the inside, and holds the pose at the teetering edge, not simply so long as we look but with the promise to continue do so even beyond our looking. These paintings are not performing for us. I have been thinking about works of art occupying empty rooms, addressing that emptiness, so many paintings seems to require the gaze, making the viewer a part of the work’s balance, but Harp-Strum is self-sufficient; the tenuousness of bodies poised at the edge of joy is sustained not by any audience, but by each woman’s counterpart in the diptych.

Two other paintings which are part of the Huntington show: Greenhouse Fantasies and The Needs Beyond—address the viewer more directly, these paintings look back. But before I go on, I would like to spend a little time with Medicine at Playtime. In the spring of 2017 Hilton Als curated a show of Alice Neel’s work. Often Neel would invite in local kids or neighbors to ‘sit’ for her. There is this way that figures pose in paintings by Alice Neel that shows it is not something they did regularly, suddenly they do not know where to put their hands, they pose in a kind of question mark ‘like this?’ And one senses that Neel always withheld something of the answer even as pressing the paint loaded brush to the canvas was a way of saying ‘yes.’ The young man in Medicine at Playtime, sits in this way, and the white of his eye glances at us, but his pupils, which invisibly center his dark irises are directed off stage, and it seems another part of his looking is directed internally: at his own thoughts and the weight and position of his body, and something supple in the face suggest he knows he is being looked at. What others have seen, he is learning to regard in himself as he both absorbs and reflects back the artist’s gaze as she traces him onto the canvas—beauty—is this? am I? are you looking?

Figure 2 – Medicine at Playtime

Look, look, look all you can…

Suddenly, in the shadow of a street, a face is held out to you, and you see…

—Rainer Maria Rilke

Even a significant form has to be traced.

—Iris Murdoch

The novelist and philosopher Iris Murdoch thought both art and love decenter the self…

“Here there is not the thin light touch of recognition but a deep gazing. (Gazing is here the master image.)” Art is for us the form of life in which this specific kind of attention, that of looking intently and steadily is most often enacted. Looking at art (such as one might encounter in the new Moma for example) is the very place where one might “tire” from looking, and in some cases as Murdoch writes: “this is the only context in which many of us are capable of contemplating at all.”

In her philosophical writings Murdoch describes a certain moment in fiction, which I think rather tightly maps to this moment in painting — she contrasts fantasy with imagination, and contrasts attending to reality with convention and neurosis. Fantasy is “an anxious, usually self-preoccupied, often falsifying veil which partially conceals the world” Reality, i.e. real people “are destructive of myth, contingency is destructive of fantasy and opens the way for imagination.”

We use our imagination not to escape the world but to join it, and this exhilarates us because of the distance between our ordinary dulled consciousness and the apprehension of the real. The value concepts are here patently tied on to the world, they are stretched as it were between the truth-seeking mind and the world, they are not moving about on their own as adjuncts of personal will. The authority of morals is the authority of truth, that is of reality.

Imagination and attending to reality both seem to entail an act of mimesis. Imagination is “truth-seeking.” Whereas convention simply obeys familiar formulae, and the neurotic work allows the author to unfold a myth about himself or the world where other people appear merely as “as organized menacing extensions of the consciousness of the subject.”

Murdoch writes “we judge the great novelists by the quality of their awareness of others.” I would like to judge painters by the same rule: by their ability to realize that something real exists other than oneself, and in their manner of enacting within the work a surrender of intention or will—or as poet T.S.Eliot phrased it—“a continual extinction of personality.”

There is something about attending to an object that exists independently of the self, and this is an attention that exists on top of that required in handling material such as paint. There are many ways this material is resistant to an artist’s attempt to use it to trace significant form and so painting is a process that requires attention and compromise. But attending to the real as subject of this process is to add to this constellation yet another connection to the world, another demand, which complicates the process in what I think is the best way possible. To really attend is to hand over control of one’s intentions complete with some inevitable object they were bound to produce, and to allow for the creation of an independent object that brings with it complex intransitive material meanings that the artist may not yet even be able to see or account for. To attend is to attempt to encounter a truth before it is even registered as a truth, to notice, and bring over something of ragged reality still ragged.

Figure 3 – Greenhouse Fantasies

Gazing is here the master image: Greenhouse Fantasies

Art and morals are, with certain provisos which I shall mention in a moment, one. Their essence is the same. The essence of both of them is love. Love is the perception of individuals. Love is the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real. Love, and so art and morals, is the discovery of reality. What stuns us into a realisation of our supersensible destiny is not, as Kant imagined, the formlessness of nature, but rather its unutterable particularity; and most particular and individual of all natural things is the mind of man.

I have thus far not mentioned one major aspect of Yiadom-Boakye’s work which I feel connects her project implicitly with Iris’s Murdoch’s. While these works have something in common with conventional figure painting, they have this major difference: they are not drawn from life, and are in fact constructions developed from found images or the artist’s imagination. This would seem to align her work with artists who impose the veil of fantasy or with the solipsistic method of the neurotic work of art (as outlined above), and yet her work is not like these either. What we do in fact have before us are ‘fictions’: characters as imaginatively constructed as those that populate Murdoch’s novels, and as such are, I think, as successful as those characters Murdoch praises in the novels she favors. They represent—to quote Murdoch—“a plurality of real persons more or less naturalistically presented” and appear to have “mutually independent centers of significance which are those of real individuals.” So that it could be said that Yiadom-Boakye “displays a real apprehension of persons other than the author as having a right to exist and to have a separate mode of being which is important and interesting to themselves: “free, independent of their author, and not merely puppets in the exteriorization of some closely locked psychological conflict of [her] own.” These ‘fictions’ in Lynette’s work require from the artist a rich experience of other bodies and a history of looking closely or they would not compel. These fictional characters are so ‘well-drawn’—and I mean that in the literary sense—that what appears is more than the shadow of the real, so that the paintings insist on their having the status of portraits corresponding to actual people in the world.

But that these are not ‘real’ people, forecloses any absolute act of recognition which I think is interesting, even important. I want to return to Murdoch’s description of looking “Here there is not the thin light touch of recognition but a deep gazing.” (emphasis mine) What is required here, because it is an artwork, is that we look intently and closely, indeterminately. And if an artwork merits such looking why not a person? What if we looked at people, ordinary people—in the street or on the subway—in this way? What if at the moment when our gaze met that of a stranger’s we held that gaze?

This holding of gaze is exactly what Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Greenhouse Fantasies offers, and I would not suggest that looking at this painting does not bring with that frisson of being ‘caught looking’ that happens with real people in the world, and I think this is in no way accidental. Recognition/identity presupposes likeness or kinship: a likeness in look or in language obscures an assumption for what it is, while in fact some superficial recognition may not be grounds to assume one does or does not mean the same way, and likeness may conceal substantial difference. Yet I think depending on who is looking, the person who appears in the painting might be distinguished as ‘someone who may resemble’ a friend, a lover, a child, a parent, a character in a film or novel; or may fail to be distinguished as anyone in particular—a mere other—with no prior associations or with associations that are fraught with assumptions and misapprehensions.

We have before us in Greenhouse Fantasies, a person made of paint, slightly larger than life size (actual life-size often reads as small when translated to the 2-D surface), glimpses of red imprimatura in the face and above the head suggest time – stages in the painting’s life: painting as an activity, like looking is an activity. The eyes of the man in the painting follow the viewer in that uncanny way some paintings have, which can seem like a sort of painter’s sleight of hand, but here operates differently and does not feel like a trick. There is always an asymmetry to the gaze, the near symmetry of the face unmakes itself under scrutiny. In Manet’s paintings, one might find just such an insistent and enigmatic gaze, but in his work there is an environment that provides respite from the gaze (and in real life we can look at our feet for instance, but in a Manet painting the artist provides any number of clearly rendered objects and persons to look at.) This is not the case in many of Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings where the backgrounds are simple color fields or vaguely rendered spaces, so there is only the face and part of the upper torso to focus on. To trace the expression, I would say that the painting portrays a gaze held at the moment before recognition, before acknowledgement, a gaze like an open question: pose quiet, lips closed but not pressed, background cast into shadow and so stripped of narratives or context. We encounter the painting as other. What does it take to hold that gaze which reveals nothing, but implies the activity of judgement? —To hold the gaze, to become implicated by it, and perchance to witness oneself fail in the gaze of the other and be found wanting? What does it mean to be seen seeing and to be held accountable—and to feel oneself accountable?

Still, we tend to think of eyes, wet and glistening like tiny pools, as the precise place where the gaze penetrates. We look into each other’s eyes; eyes affect an appearance of depth. Yet in the whites of the eyes of the man in Greenhouse Fantasies, and in numerous other works by Yiadom-Boakye, there is no application of paint by the artist, these are not tiny pools. What is visible is the bare, unaltered white of the gesso ground. As such these eyes penetrate as deep into the painting as a painting allows, by which I mean the eyes are all surface, they stop literally at the surface of the painting and do not pretend to go any deeper.

They seem to call a lie to any idea that we can see into another person—this fallacy of the inner—as if knowledge of the inner person could be sustained by evidence of some external likeness, as if these external clues provided evidence of ‘what a person was thinking’ or ‘who they were,’ and that degrees of visual difference (from the self, from the familiar) corresponded to degrees of intellectual, moral or emotional difference. Yiadom-Boakye’s painting insists on the opacity of the other.

Beyond the 2015 exhibition, Forces of Nature—which Hilton Als curated for Victoria Miro Gallery in London, which reflects on the presence or absence of the human form in artistic ‘depictions’ of nature and our vexed relationship with the natural world—much of Hilton Als’ curatorial projects focus explicitly on portraits while also serving as “portraits” of artists whose work engages in the particularity of being embodied. An earlier show Self-Consciousness (2010) at VeneKlasen/Werner gallery in Berlin, drew into question the forms a portrait could take; and The Hilton Als Series at the Yale Center for British Art lead with the figurative painter Celia Paul (2017), followed by Yiadom-Boakye (2019), and Njideka Akunyili Crosby (planned for 2021). In addition are two shows that took place at David Zwirner Gallery in New York: Alice Neel, Uptown (2017), which focused on Neel’s portraits of people of color; and God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, (2019).

In my mind I can hear the advice which Rilke wrote in a letter to his wife—the artist Clara Westhoff Rilke—“Look, look, look all you can…” Als could take us anywhere words could lead, but clearly there is something that Als wishes to look at that extends beyond anything he might write. “Historical change is (in part and fundamentally) change of imagery” writes Iris Murdoch.

In his recent New Yorker article: Carolyn Forché’s Education in Looking (April 6, 2020), Als quotes the poet as she describes witnessing certain occasions of blindness amongst the sighted, witnessed not only in the behavior of others but also in her own, and she writes:

[W]e Americans . . . tend to register perceptions without codifying them in any political, historical, or social way. There’s no sense of what creates or contributes to or who benefits from a situation. And I’m not talking about a prescriptive political ideology now . . . [but] a process of understanding.

Looking is not equivalent to understanding. We ‘see’ only what we know how to describe, and knowing how to describe clarifies in turn what we can see. The instant you try to describe—to trace something of the world with words or a pencil—this expression is already ordering, classifying, valuing. Perception is never neutral; looking is valuing. For Murdoch, a central metaphor for moral awareness is visual awareness. That painters such as Yiadom-Boakye, Celia Paul and Alice Neel must either leave-open or fill-in the spaces that exist in between the known and the known, still these space must be accounted for, and this is key to these artists tease out our confidence in our own perceptions. They teach us that we have something yet to learn about how to look.

Als closes his recent article with an excerpt from “What Comes”—Forché’s final poem in her book In the Lateness of the World (2020)—which ends with these lines: “… there is nothing / that cannot be seen / open then to the coming of what comes”

———

Iris Murdoch. “Fact and Value” and “Imagination,” in Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals. (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books 1993). 25-56, 308-347.

Iris Murdoch. Various essays – see below, Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature, edited by Peter Conradi, foreword by George Steiner. (New York: Penguin, 1997)

“The Sublime and the Good” 205-220

“Against Dryness” 287-295

“The Sublime and the Beautiful Revisited” 261-286

“The Sovereignty of Good Over Other Concepts” 363-385

Iris Murdoch. “Nostalgia for the Particular”. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, New Series, Vol. 52 (1951 – 1952), 243– 260. Oxford University Press on behalf of The Aristotelian Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4544504